And what is it? From social pressure to hide menstruation to free-bleeding and first period parties, menstrual etiquette is changing.

For generations, people with periods everywhere have been ushered into feeling like menstruation should be a source of shame, social anxiety, and embarrassment. Living with the pressures of silencing our menstrual cycles has led to long-term behavioral changes which affect our relationships with friends, family, lovers and ourselves. These demands on menstruators began with myths and beliefs that date back to primitive human societies around the globe which rendered periods taboo, even dangerous. The why and when menstruation became taboo, its history creating period stigma, and the long-lasting impacts on society are still felt today, influencing our ‘menstrual etiquette’.

What is menstrual etiquette?

Coined by Sophie Laws in her 1990 book, Issues of blood: the politics of menstruation, ‘menstrual etiquette’ refers to a series of (mostly) unwritten rules that menstruators have been expected to abide by to hide the shame of our periods and keep menstruation invisible. In other words, menstrual etiquette implies the ways we can ‘menstruate politely’ by shielding others from the discomfort of seeing, knowing or hearing about monthly bleeding. The bottom line of menstrual etiquette is to keep all evidence of periods out of sight and mind.

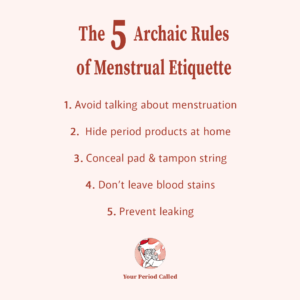

What are the rules of menstrual etiquette?

Since society has been uncomfortable with the very idea of the menstrual cycle and period blood for thousands of years, even mentioning it has been deemed offensive. So in order to make others feel more at ease, menstrual etiquette details the language we should use to refer to menstruation (enter euphemisms like shark week and aunt flow), who and where we can talk to about it (whispering in the bathroom), which products we should use, and even how to get those products, carry them around and store them. The main idea: in order to be accepted as “normal” in society, we need to hide our periods at all costs. This idea has been so deeply internalized that we often even hide our experience from other menstruators or even our closest loved ones!

Here are a few of the rules:

- Avoid talking about menstruation (especially in public and with men)

- Hide menstrual products at home or deep in your bag

- Make sure that the outline or bulkiness of your pad is concealed and tampon string is tucked in

- Don’t leave blood stains on anything

- Prevent leaking through your clothes

Menstrual etiquette imposes a double burden on menstruators to keep periods invisible, even in places where that may be very difficult or inconvenient - such as in bathrooms with poor facilities or no trash cans. If you’ve ever felt the urge to hide that crinkly sound a pad or tampon makes when you open it, you know what we mean.

Who follows the rules of menstrual etiquette?

Scientific studies from the 80s through the mid-2010s have found the rules of menstrual etiquette to be alive and well. Interview participants in a 2014 study talked about how they hide their period products at home and on the go, and take precautions to conceal bleeding both from men and women in various social contexts (like train stations without a bathroom, stores, swimming pools, and in sexual situations). They said that the stakes are high if someone finds out, resulting in feelings of shame and embarrassment. One 2002 study discovered that a sign that a person is menstruating (for instance, if a tampon falls out of their bag) will lead to negative feelings towards them. The study further concluded that the witness(es) may try to avoid this human who is already dealing with enough without the judging eyes!

“I decided to just bleed freely and run. And I knew it was a radical choice because we are not taught to prioritize our own comfort over the comfort of others, we never have been,”

Madame Gandhi.

Repetition of menstrual stigma over the years through cultural discourse and corporate advertising has reinforced the feeling that we should follow the rules of menstrual etiquette. There are many examples we will talk about below that encourage insecurities like worrying about leaking, smelling or showing in some other way that we’re menstruating. At least until quite recently, these were the norms we lived by, often without questioning their purpose or potential harm. So where are we today? Where has the dialogue around periods modernized?

Is menstrual etiquette still a thing?

Over the last several years, society has become more open to both talking about and showing periods publicly, a stark contrast to the rules of menstrual etiquette. Here are a few examples:

Kiran Gandhi and free bleeding

Musician, runner, activist, and all-around badass menstruating human, kicked off this new way of thinking about periods when completing the 2015 London Marathon while “free bleeding” - or not using any products to absorb her menstrual blood - and received widespread media coverage for her bravery to combat the stigma.

In this video about Talking Periods in Public, she explains her decision to free bleed and why we shouldn’t feel ashamed about leaks.

Rupi Kaur’s period Instagram photo

Later that year, Rupi Kaur famously posted this Instagram photo of her bleeding in bed which got removed TWICE for “violating community guidelines” before she was allowed to keep it up. The image is now viral and can be stumbled upon regularly across the internet, we’d bet you’ve already seen it!

Year of the period

These events combined with the rise of period tracking apps, activism against the tampon tax, viral hashtags and more led to BuzzFeed naming 2015 the “Year of the Period”. Buzzfeed’s moment helped catapult the menstrual movement even further and public discourse began chipping away at age-old taboos by questioning and challenging period etiquette.

Period parties: celebrating first periods

Now, far from feeling fearful and ashamed by the onset of menstruation, period parties are “a thing” now to celebrate the first period, garnering attention when this adorable tweet went viral.

Brooke started her period today & my family is super extra ?? pic.twitter.com/ed14gNrgKf

— Autumn Shea (@autumn1shea) January 10, 2017

Research shows that the mindset towards reproductive health is shifting among the younger generations, who feel more positively about their periods and are also more open to discussing them than any prior generation. In 2019, Lunette conducted a survey with 2,000 menstruators aged 18 to 38 and found that around 80% of Gen Zers, or people born between 1997 and 2012, don’t think of periods as a taboo topic. They don’t view menstruation as gross and don’t see it only as a women’s issue, but one that should be talked about openly, which includes non-menstruators! How’s that for progress?!

But, we still have a ways to go: 65% of those surveyed by Lunette agree there is still menstrual shame in society today. This is caused in part by the fact that some of the big corporate brands are STILL emphasizing discretion and secrecy in their marketing and product development.

Menstrual etiquette and company branding

In 2020, Tampax launched a new line of tampons - the Tampax Pearl Compak - which feature silent wrappers so no one needs to find out when we open a tampon in the bathroom. On their website they write, “TAMPAX Pearl Compak tampons offer you a combination of comfort, protection and discretion, all in one pack!” The company received a good amount of backlash for this “innovation” which Guardian journalist Sophie Elmhirst calls “increasingly at odds with the times”.

Tampax, one of the largest corporate giants dominating the menstrual care market, isn’t alone in not-so-subtly telling menstruators to keep quiet about their periods. Always, another brand owned by Proctor & Gamble, advertises pads with “quiet wrappers for discretion” and O.B. talks about “Women’s need for discreet yet reliable protection” on their site. It’s language like this that has kept the stigmatization of periods alive over the years and created social pressure to stick to the rules of menstrual etiquette -- strengthening the belief that menstruators shouldn't talk about their experience.

Menstrual etiquette and the workplace

Today, menstruators still don’t feel comfortable discussing periods in professional situations and take measures to hide their periods - for instance by shoving a tampon up our sleeve to walk the bathroom, or finding other creative ways like sticking it in an empty coffee cup. Lunette’s survey reports that 33% of Gen Zers aren’t comfortable talking about periods with all genders. We also may make up excuses besides our periods as to why we have to miss work. For advice on how to talk about periods with men and in professional environments, check out our article here.

National menstrual leave policies already exist in Japan, Taiwan, China, South Korea, Indonesia, Zambia and Mexico.

India, for example, is a country which holds very strong period taboos that impact many aspects of a menstruator’s life (including our writer Praksha). However, in 2020, food delivery company Zomato instated a ‘period leave’ policy which granted up to 10 paid days off each year. While their goal was to reduce shame and stigma surrounding menstruation, it ignited a fierce debate in the country and worldwide: proponents applauded the policy as long overdue while others called it discriminatory and anti-feminist. National menstrual leave policies already exist in Japan, Taiwan, China, South Korea, Indonesia, Zambia and Mexico.

We can also see evidence of menstrual etiquette today in regards to where we store our period products at home. I conducted interviews with 9 women living in Berlin, Germany about their feelings towards the current changing culture around menstruation. While they said they generally feel comfortable discussing periods, 6 out of 9 normally hide period products in their bathroom cupboard rather than keeping them out in the open. The package design appears to play a big role in this, however, as 8 out of 9 participants said they would gladly display beautifully designed boxes like those of Berlin startups The Female Company and Einhorn.

While menstrual etiquette still exists in some forms, evidence shows the great strides we’re making towards changing the narrative surrounding periods. We can be proud of how far we’ve come and look forward to the next steps knowing we’re on the right path!

You can read another one of Kayla's articles on when and why menstruation became taboo here!

Cover photo image from Vulvani.

_____________________

References:

Alzate, J. (2013). The Menstrual Closet: Analysis of Representation of Menstruation in Japanese and Columbian Advertisements for Feminine Hygiene Products. ICU Comparative Culture, No. 45, p. 29-59.

Beck, J. (2015, June 1). Don’t Let Them See Your Tampons. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/06/dont-let-them-see-your-tampons/394376/

Berenson, C. (2014). Pondering periods: Young women talk about menstruation in the age of menstrual suppression. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27381

Kissling, E. (1996). Bleeding out loud: Communication about menstruation. Feminism & Psychology, Vol. 6, No. 4, p. 481-504.

Kroutroulis, G. (2001). Soiled identity: Memory-work narratives of menstruation. Health, Vol. 5, No. 2, p. 187-205.

Laws, S. (1990). Issues of blood: The politics of menstruation. London: MacMillan.

Lee, J., & Sasser-Coen, J. (1996). Blood stories: Menarche and the politics of the female body in contemporary U.S. society. New York: Routledge.

Lunette. (2019). Going With The Flow: Gen Z vs Millennials. Lunette Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.lunette.com/blogs/news/going-with-the-flow-gen-z-vs-millennials

Martin, K. A. (1996). Puberty, sexuality, and the self: Boys and girls at adolescence. New York: Routledge.

Roberts, T. A. et. al (2002). “Feminine Protection”: The Effects of Menstruation on Attitudes Towards Women. SAGE Journals. Vol. 26, No. 2, p. 1310139. (Abstract Only). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.00051

Roberts, T. A. (2004). Female trouble: The Menstrual Self-Evaluation Scale and Women's Self-Objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1, Issue 7, 22-26.

Schooler, D et. al. (2005, November). Cycles of Shame: Menstrual Shame, Body Shame, and Sexual Decision-Making. The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 42, No. 4, p.324-334.

Popular reads on YPC

How to Talk About Your Period With Men

Talking about periods with male friends and co-workers doesn’t have to feel like unleashing landmines.

Read moreWhy and When Did Menstruation Become Taboo?

From the Yukon to Greece, taboos around menstruation have been around for ages and still…

Read moreSocial Media’s Important Role in Reducing Period Stigma

From the explosion of period art, to serving as an activist platform in the menstrual…

Read more