From the Yukon to Greece, taboos around menstruation have been around for ages and still carry consequences.

Pretty much from the beginning of time, periods were a taboo topic, and still are in many regions of the world. The menstrual taboo refers to the social stigma and shame surrounding periods, including discussing periods in public and caring for a menstruator’s needs.

Swedish journalist Anna Dahlqvist interviewed menstruators from around the world for her 2018 book: It’s Only Blood, and from the U.S. to Uganda, Sweden to Bangladesh, she found period shame to be a universal phenomenon. It seemed the understanding that menstruators should keep quiet about their periods was found in all corners of the globe.

Sinja Stadelmeier, co-founder of The Female Company, a Berlin startup delivering organic period products via subscription, commented on the taboo in an interview saying how, “Five years back, nobody talked about periods and it was nothing you discuss, even with friends, but instead a topic you whisper about behind closed doors.”

In recent years, we can see immense progress surrounding periods in Western culture, but we’ll get to that. First, let’s take a trip down memory lane to explore some of the wacky myths and beliefs surrounding menstruation spanning cultures, history and time.

Where did period taboos come from?

The menstrual taboo has deep historical, religious and cultural origins. Evidence of it can be found dating back to the very beginnings of human civilization.

In many ancient societies, menstruating women were thought to emanate a dangerous supernatural power. Some men believed menstruating women controlled the cycles of the moon, seasonal change, tides, and darkness at night, or that menstrual blood had a negative effect on organic materials (nope, only underwear). So, what did primal men do? They created taboos around periods to warn their comrades to avoid women and the mysterious dangers that come with monthly bleeding.

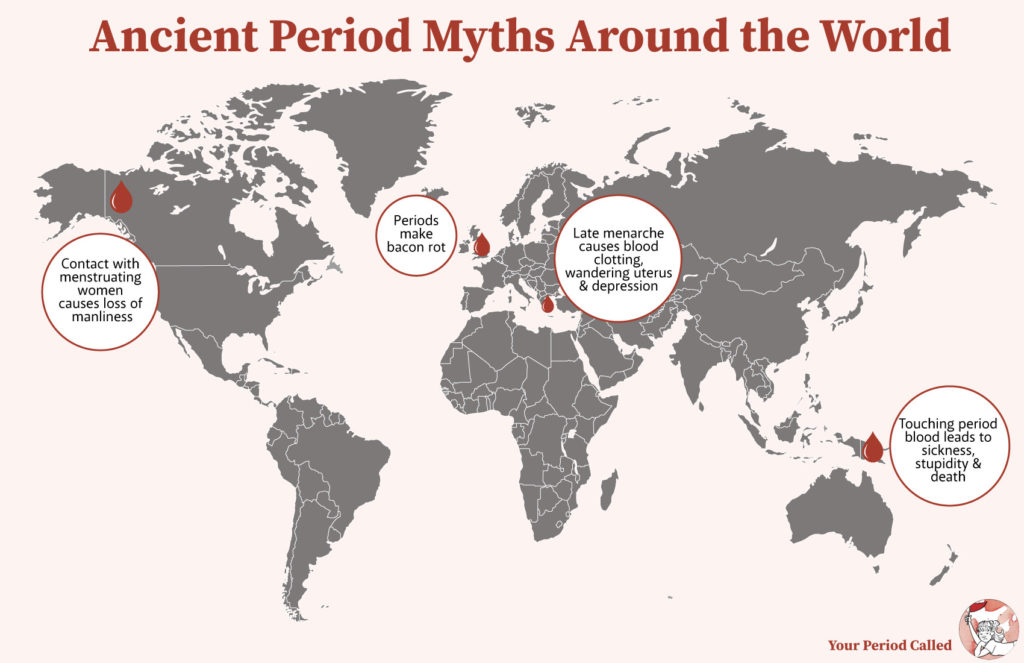

Primitive societies such as the Mae Enga tribe in Papua New Guinea believed that if men touched period blood they would get sick, stupid, darker skinned, and worst case, even die! The Tinne indigenous people of the Yukon Territory in Canada weren’t quite that extreme, but thought that having contact with a menstruating woman would make a man lose his manliness.

Moving over to Europe, the ancient Greeks thought that when menarche (the first period) happened late, it would cause blood clots around the heart, the uterus to wander around the body, swearing and suicidal depression...yikes! During medieval times, people believed that if a penis touched period blood it would burst into flames, and a child conceived while menstruating would either be possessed by the devil, deformed...or a redhead.

Some also thought that menstruators should not be allowed to see light, touch water, go near growing crops, and my personal favorite, that we cause bacon to rot!

Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism have all negatively portrayed menstruation and its effects on women, describing both periods and menstruators as unclean and impure. The Quran warns men to stay away from women while they are on their periods. Catholic doctrine blames Eve for getting the boot from the Garden of Eden, and menstruation serves as a painful reminder and punishment for her sin. Other religions prescribe cleansing rituals, like the Mikvah baths in Judaism, or prohibitions on activities like sex, cooking, or visiting places of worship.

But believe it or not, beliefs around menstruation in the past weren’t all bad. In fact, some cultures considered period blood to be sacred, a fertilizer for crops, and even a cure for illness.

Why do we still have period taboo?

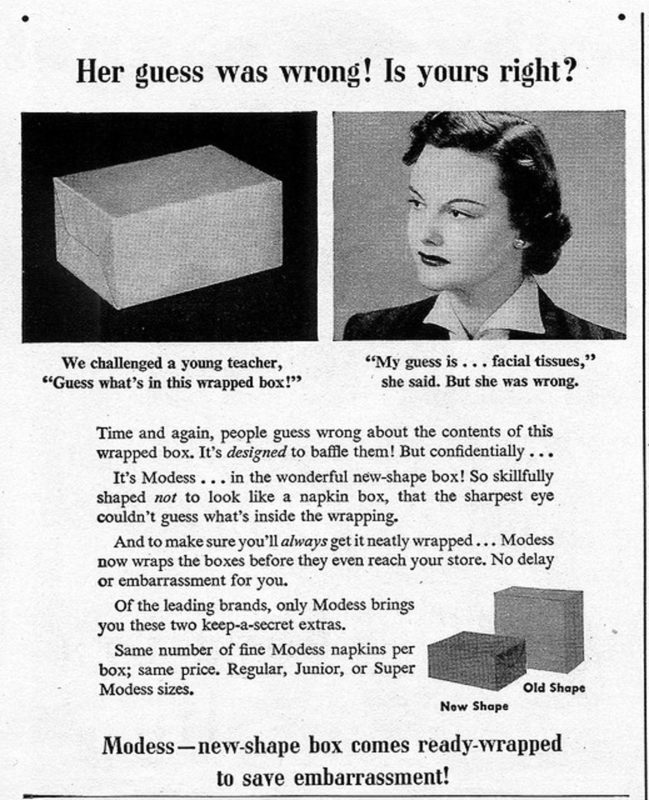

The main discourse throughout the 19th, 20th and early 21st centuries depicted periods as a “hygienic crisis” that should be kept secret at all costs. This message was passed along via corporate marketing. From when period products entered the mass market, brands showed us just how embarrassing periods really are.

Take a look at this newspaper ad from the early 20th century:

What’s-In-The-Shame-Box

What’s-In-The-Shame-Box

Photo credit: Bustle

Research on period TV commercials found that advertisers portray periods in a negative light and as a problem, causing body odor, a feeling of “unfreshness”, sleeping problems and embarrassing leaks. Basically, periods have been shown as a dirty monthly incident which causes us to feel anxious, guilty and unconfident. These problems can of course be fixed by purchasing their products - please save us from ourselves!

Why is period taboo bad?

Period stigmatization has resulted in very real, and even dangerous, consequences for society, including social exclusion, economic disparity, pollution, health issues and even death.

In some rural villages in Nepal, menstruating women are still exiled to huts away from their communities until the end of their period despite the tradition called chhaupadi being banned in 2018. This practice to this day has resulted in the deaths of several women each year. Menstruators are also barred from entering Eastern Orthodox churches and receiving communion. In Japan, Shintos can’t visit temples or climb sacred mountains during menstruation. In some cultures, the first period symbolizes the beginning of womanhood, and comes as a precursor to genital mutilation or forced child marriage.

Did you know that the word “taboo” originates from the Polynesian term “tabua”, which also means menstruation?

Periods are also the major reason that girls miss school in developing countries. Social shaming and lack of access to menstrual care products, private toilets and clean water all factor into girls missing out on their right to an education. According to UNESCO, only 50% of Kenyan girls have access to pads. In Nepal and Afghanistan, 30% of girls have skipped school during menstruation, while in India, 20% drop out completely. When this happens, girls are less likely to go back to school later on and they become more vulnerable to early marriage, rape or violence. Not to mention the missed economic and social opportunities from dropping out of school at a young age, affecting both their personal and their country’s prosperity in the long term. And it gets worse. In 2017, a 12-year old Indian girl committed suicide after her teacher allegedly shamed her for a period stain on her school uniform in front of the entire class.

What are the psychological consequences of period taboos?

Beyond these social impacts, there have also been psychological consequences. For example, since it has been etched into our psyche for generations that periods are disgusting this means we are too for having them! As Nadya Okamoto discusses in her book, Period Power, the stigma has led to the belief that periods make people incapable, emotionally out-of-control, and an annoyance for men, as well as the cause of a menstruator’s bad mood and problems in the bedroom (not likely, bud). For centuries people with periods have been made to feel weak, ashamed, dirty and unreliable all because we bleed monthly.

Scientific studies dating from the 80s through 2017 have confirmed that menstruation leads to feelings of shame, contamination, and self-disgust. Those interviewed said they don’t want others to see them with a menstrual product, or in the absolute worst case, get caught with a period stain. One 2005 study by Deborah Schooler and fellow researchers found a link between menstrual shame and body shame, leading to less sex and unsafe sexual behavior.

How do menstruation taboos affect how we act?

The taboo led to the creation of a series of rules for how we should act during our periods, most important of which being to not talk to anyone about it (hence all the silly period euphemisms) and not show any evidence that you’re on your period. Did you know that the word “period” was first used in a TV commercial only in 1985? Do you know who it was? We do a deep dive on periods and TV here.

In the early 2000s, a new trend began - to choose not to have a period at all - through new birth control pills like Seasonale. Researchers argue that this reinforced the period stigma, making us think that periods are an unnecessary burden that can be avoided, if we so choose.

Lastly, stigmatization has contributed to period poverty and the “tampon tax”, or the luxury tax placed on menstrual care products, lack of innovation leading to huge pollution of our water supplies and landfills, gender inequality and even health issues. Poor menstrual hygiene due to lack of education can lead to problems like late diagnosis of cervical cancer and certain reproductive diseases.

Needless to say, the menstrual taboo and unwillingness to discuss periods has had drastic repercussions across the world.

Taboos and menstruation today

Thankfully, the period tides are turning and, at least in Western culture, periods are becoming more accepted as a normal and appropriate topic of public discussion. Tons of new period startups have launched in recent years, many of them focusing on sustainable menstrual care and changing the conversations we’re having about periods. There’s a period sustainability checklist that you can use to play your part in having a sustainable period.

Worldwide, countries have been tossing out the tampon tax, and Scotland is leading the way by making period products completely free in public places. We are definitely moving in the right direction and can be hopeful for the future that it will continue to go this way!

The more we discuss periods, the more we can dispel these old myths and cultural taboos and move towards general acceptance of menstruation and everyone who menstruates.

You can read more about Kayla, our menstrual information badass and YPC contributor, on our Our Story page.

____________

References:

- Alzate, J. (2013). The Menstrual Closet: Analysis of Representation of Menstruation in Japanese and Columbian Advertisements for Feminine Hygiene Products. ICU Comparative Culture, No. 45, p. 29-59.

- Barak-Brandes, S. (2011, Jan.). Internalizing the taboo: Israeli women respond to commercials for feminine hygiene products. Observatorio. Vol. 5, No. 4. p. 49-68. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283249422_Internalizing_the_taboo_Israeli_women_respond_to_commercials_for_feminine_hygiene_products

- Bobel, C. (2010). New Blood: Third-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP.

- Bobel, C. & Kissling, E. (2011). Menstruation Matters: Introduction to Representations

- of the Menstrual Cycle, Women's Studies: An inter-disciplinary journal, Vol. 40, No. 2, p. 121-126). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2011.537981

- Coult, A. (1963). Unconscious inference and cultural origins. American Anthropologist 65: 32-35.

- Delaney, J. et. al (1988). The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. Chicago: University of Illinois Press

- Elmhirst, S. (2020, Feb 11). Tampon wars: the battle to overthrow the Tampax empire. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/feb/11/tampon-wars-thebattle-To-overthrow-the-tampax-empire

- Guterman, M. et al. (2007). Menstrual Taboos Among Major Religions. The Internet Journal of World Health and Societal Politics, Vol. 5, No. 2, p. 1-7.

- Hampton, J. (2017, May 2). The taboo of menstruation. Aeon. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/throughout-history-and-still-today-women-are-shamed-for-menstruating

- Lee, J., & Sasser-Coen, J. (1996). Blood stories: Menarche and the politics of the female body in contemporary U.S. society. New York: Routledge.

- Kaczmarek, M. & Trambacz-Oleszak, S. (2016, May). The Association Between Menstrual Cycle Characteristics and Perceived Body Image: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Polish Female Adolescents. Journal of Biosocial Science, Vol. 48, No. 3, p. 374-390.

- Kane, K. (1990, January). The Ideology of Freshness in Feminine Hygiene Commercials. Journal of Communication Inquiry. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/019685999001400108

- Kissling, E. (1996b). Bleeding out loud: Communication about menstruation. Feminism & Psychology, 6(4), 481-504

- Martin, K. A. (1996). Puberty, sexuality, and the self: Boys and girls at adolescence. New York: Routledge.

- Meyer, M. (2005). Thicker Than Water: The Origins of Blood as Symbol andRitual. New York: Routledge.

- Nicole, W. (2014, March). A Question for Women's Health Chemicals in

- Feminine Hygiene Products and Personal Lubricants. Environmental Health Perspectives. DOI: 10.1289/ehp.122-A70

- Okamoto, N. (2018). Period Power: A Manifesto for the Menstrual Movement. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Plan International UK (2017, December 20). Research on Period Poverty and Stigma. Plan UK. https://plan-uk.org/media-centre/plan-international-uksresearch-on-period-poverty-and-stigma

- Period Positive. (n.d.). Our Ethos. Period Positive. Retrieved from https://periodpositive.wordpress.com/our-ethos/

- Rihtaršič, T. & Rihtaršič, M. (2017). Model of Consumer Behavior – Feminine Hygiene.

- Economics. Vol. 5, No. 1. P. 125-136. DOI 10.1515/eoik-2017-0015

- Roberts, T. A. (2004). Female trouble: The Menstrual Self-Evaluation Scale And women's self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28( 1 )7 22-26

- Rubio, M. & Speck, B. (2009, December). Constructing female identities through feminine hygiene TV commercials. Journal of Pragmatics. Vol. 41, No.12, p. 2535-2556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.04.005

- Schooler, D et. al. (2005, November). Cycles of Shame: Menstrual Shame, Body Shame, and Sexual Decision-Making. The Journal of Sex Research, Vol. 42, No. 4, p. 324-334.

- Scultz, C. (2014, March 6). How Taboos Around Menstruation Are Hurting Women’s Health. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-taboos-around-menstruation-are-hurting-womens-health-180949992/

- Weiss-Wolf, J. (2017). Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity.New York: Arcade Publishing.

- Woods, C. (2013). Repunctuated Feminism: Marketing Menstrual Suppression Through the Rhetoric of Choice. Women’s Studies in Communication, Vol. 36, No. 3, p. 267-287. doi:10.1080/07491409.2013.829791

- Vaughn, E. (2019). Menstrual Huts Are Illegal in Nepal. So Why Are Women Still Dying in Them? NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2019/12/17/787808530/menstrual-huts-are-illegal-in-nepal-so-why-are-women-still-dying-in-them?t=1608286279192

Popular reads on YPC

How to Talk About Your Period With Men

Talking about periods with male friends and co-workers doesn’t have to feel like unleashing landmines.

Read moreWhy and When Did Menstruation Become Taboo?

From the Yukon to Greece, taboos around menstruation have been around for ages and still…

Read moreSocial Media’s Important Role in Reducing Period Stigma

From the explosion of period art, to serving as an activist platform in the menstrual…

Read more